By Hannah Lincoln & the M3 Team

Hannah Lincoln is the Lead China Subject Matter Expert at Two Six Technology’s Media Manipulation Monitor (M3). M3 tracks Chinese government manipulation—such as censorship, propaganda, and inauthentic amplification—of traditional and social media, as well as other types of data. Our system provides a unique quantitative look at the PRC’s objectives, sensitivities, and vulnerabilities, which we uncover as we monitor what information it seeks to control, silence, and spread online—at home and abroad.

This is Part 1 of a series of posts examining patterns in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) government’s online behavior.

Official PRC global messaging is largely risk averse, as political pressure inside the PRC disincentivizes diplomats and state media outlets from messaging early or provocatively in response to world events, including US actions. This creates space for US messengers to spread US-aligned narratives in the information space while Chinese bureaucrats await official guidance.

What the data shows: Based on a review of online content and narrative manipulation from PRC officials and state media (“official PRC messaging”) and inauthentic pro-PRC messaging in the Chinese and global information environments between 2020–2023, M3 identified Beijing’s risk aversion wherein:

- Insight 1: The PRC’s responses to current events can be slow and influenced by the PRC’s internal politics, indicating gaps in their global messaging apparatus.

- Insight 2: The PRC does more overt messaging about its soft power than any other single topic—including anti-US narratives.

- Insight 3: In China’s own information environment, controlling narratives around China’s internal affairs is top priority, indicating Beijing sees domestic discontent as a greater threat than foreign pressure.

- Insight 4: Inauthentic, pro-Beijing accounts frequently push more controversial versions of Beijing’s narratives, suggesting official PRC messaging channels do not want to risk diplomatic pushback.

Insight 1: The PRC’s responses to current events can be slow and influenced by the PRC’s internal politics, indicating gaps in their global messaging apparatus.

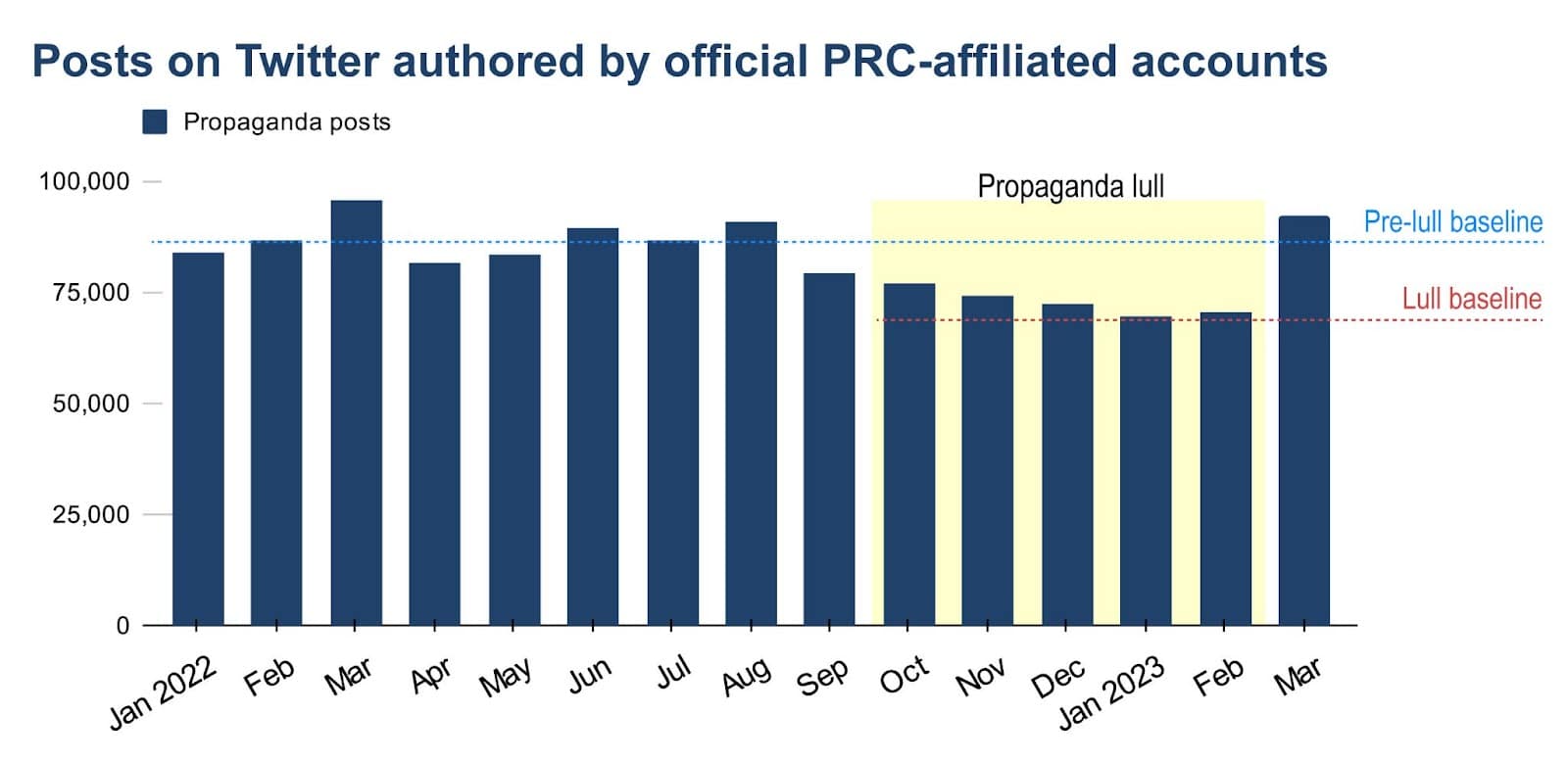

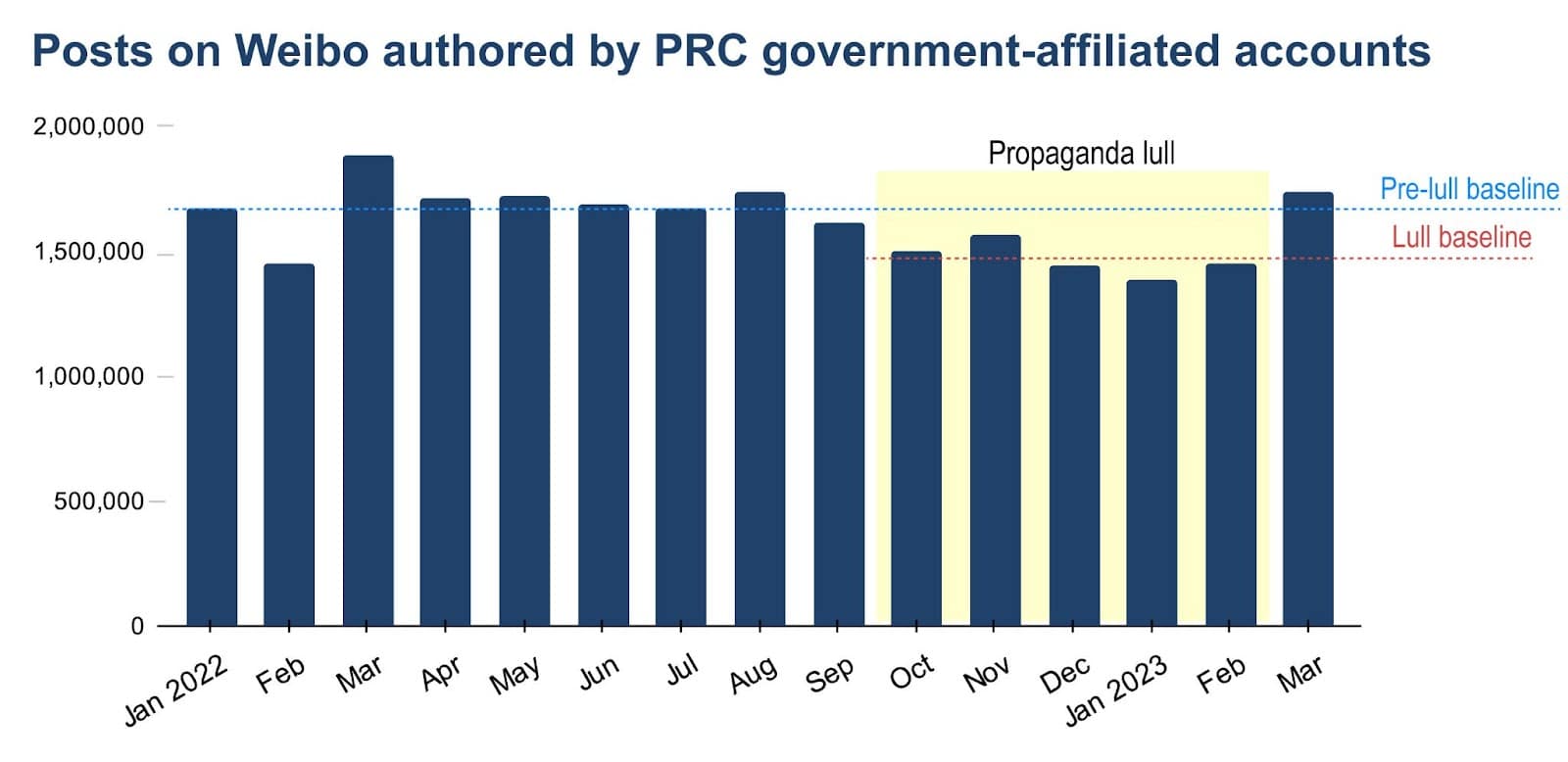

PRC messaging on global social media dropped from October 2022–February 2023, suggesting that Beijing’s propagandists paused efforts while awaiting new marching orders coming out of the Two Sessions congressional meeting in March. Once the new congressional term began during 4–11 March, government-authored post volumes on Twitter and Weibo returned to pre-lull baselines. (Figures 1 and 2)

Figure 1

Figure 2

Delayed messaging responses: During the government transition and personnel reshuffling of October 2022–February 2023, M3 tracked a few instances of delayed PRC responses to global events. The delayed responses are not necessarily a result of the government transition and it is possible that they would have occurred during non-transition times.

- During the propaganda lull, M3 captured at least two instances of missing or delayed PRC responses to global events:

- PRC Twitter accounts authored only one post in response to charged remarks by a US Representative on 28 February, who accused the Argentine government of making a “pact with the devil” in its cooperation with Beijing.

- PRC Twitter accounts authored eight posts responding to a 20 January The Wall Street Journal investigative report on Chinese-built infrastructure projects in Ecuador and other countries. These posts occurred from 22–24 February, more than a month after the article’s publication.

Insight 2: The PRC does more overt messaging about its soft power than any other single topic on Twitter.

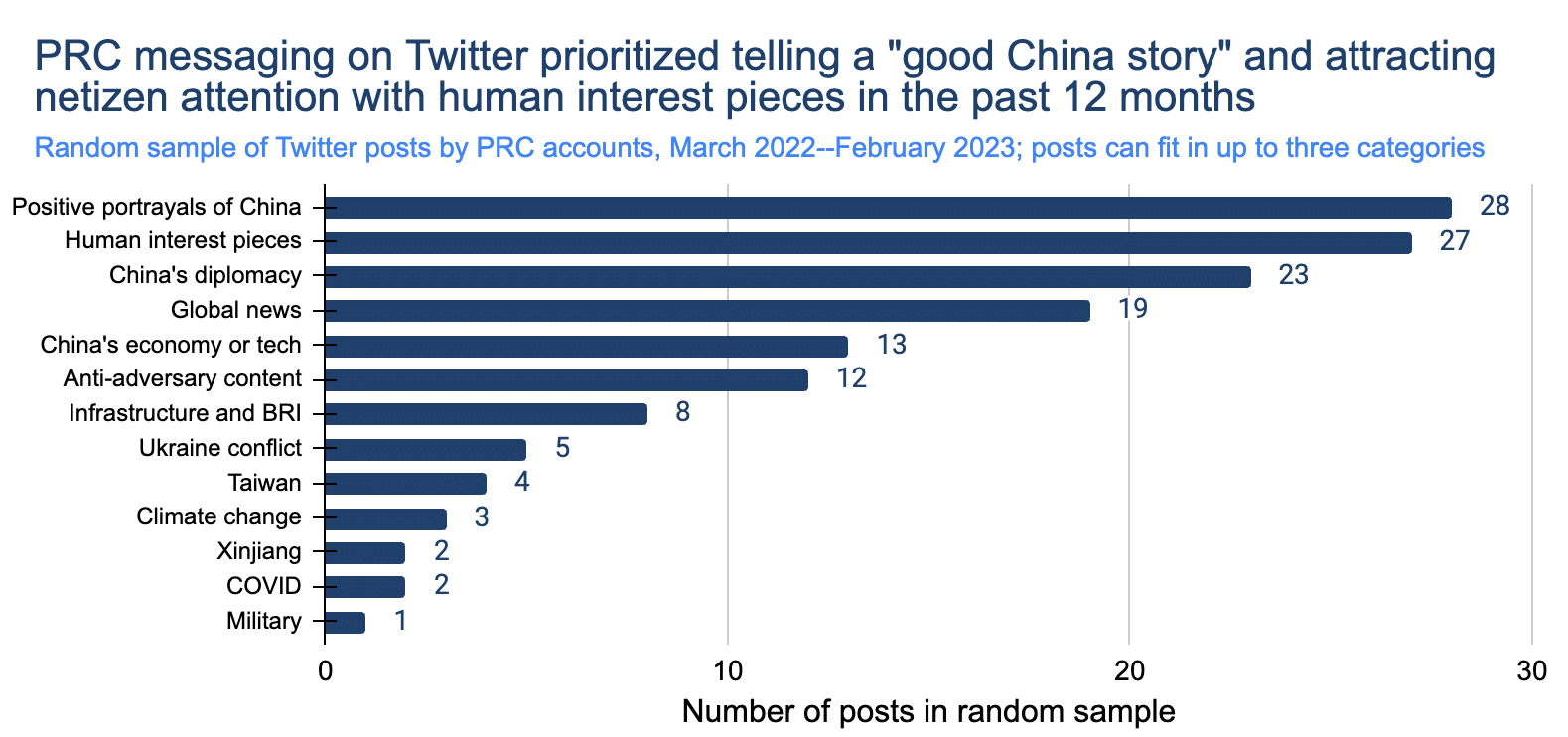

In the past year, the PRC prioritized positive portrayals of China to counter perceived bad publicity in the global information environment. PRC messaging on Twitter worked towards Beijing’s goal of “telling China’s story well.” Xi introduced this messaging strategy in 2013 to counter perceived negative portrayals of China with human interest pieces about Chinese culture instead of with propaganda about China’s governance or economic models.

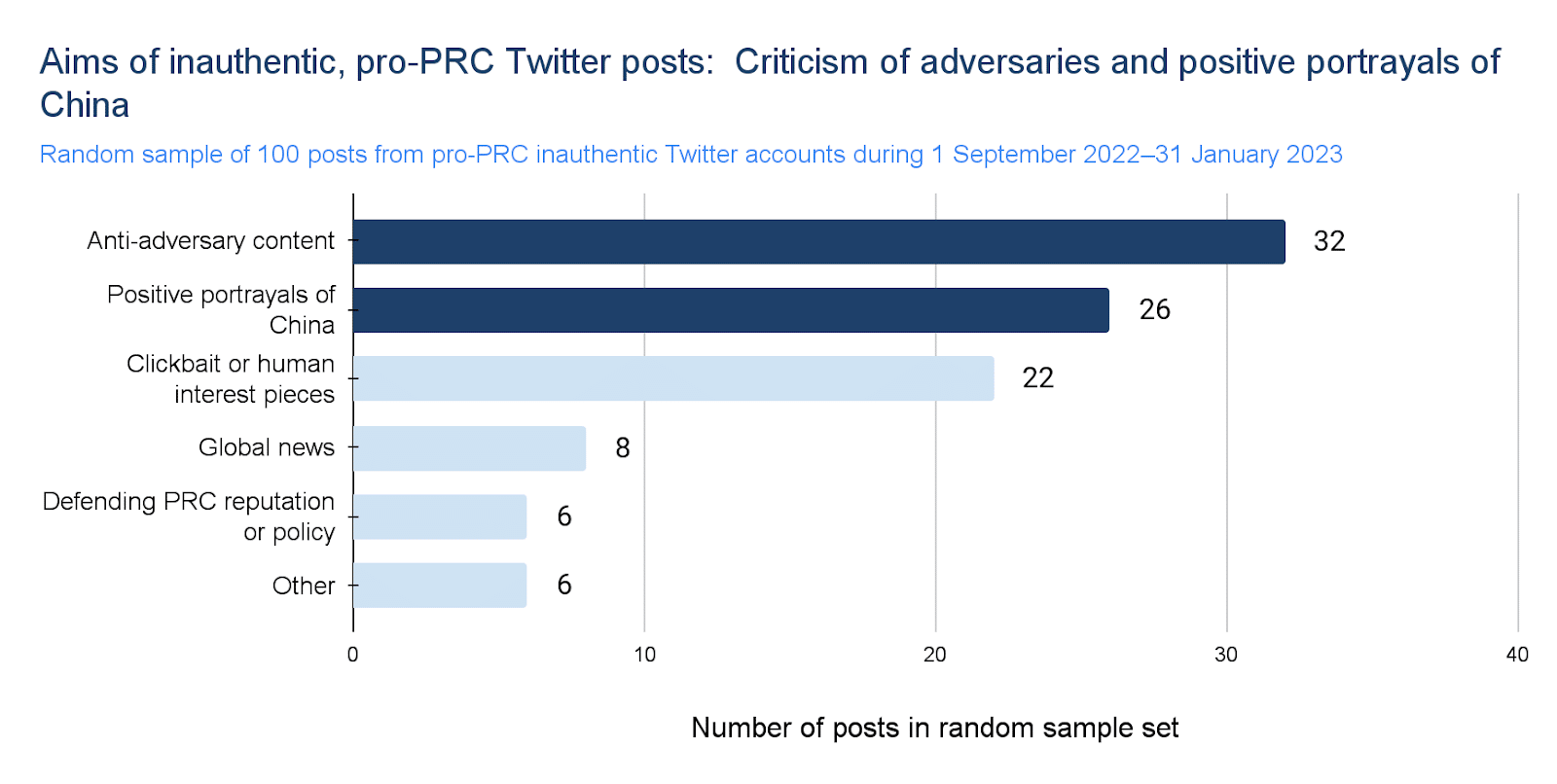

- Official and inauthentic Twitter accounts promote soft power content. About 30% of content authored by official PRC Twitter accounts and 25% of content by inauthentic, pro-PRC Twitter accounts includes positive portrayals of China. (Figures 3 and 4)

- PRC accounts use human interest pieces to attract netizen attention and bring to life positive portrayals of China. Of the 28 “positive portrayal of China” posts identified in a random sample of official PRC posts, 15 included photos of Chinese scenery and food or features about Chinese history and culture. (Figure 3)

- Official PRC messaging on Twitter mentions the US about 10% of the time, making it a less-frequently occurring topic than China’s soft power or diplomacy-related content. About half of these US-related posts portray the US negatively; the other half is mostly factual and neutral news occurring in or relating to the US.

Figure 3

Figure 4

PRC accounts on Twitter, including both officially affiliated and inauthentic, pro-Beijing accounts, do not frequently discuss democracy in direct terms, instead relying on negative portrayals of the US and its allies to undermine US influence globally.

- PRC and pro-PRC accounts did not frequently discuss democracy, instead relying on criticism of the US and its allies to undermine a US-lead liberal world order. Less than one percent of posts by official PRC accounts and inauthentic, pro-PRC accounts mentioned the word “democracy” in at least one of six languages in the past six months.

Insight 3: In China’s domestic information environment, controlling narratives around China’s internal affairs is top priority.

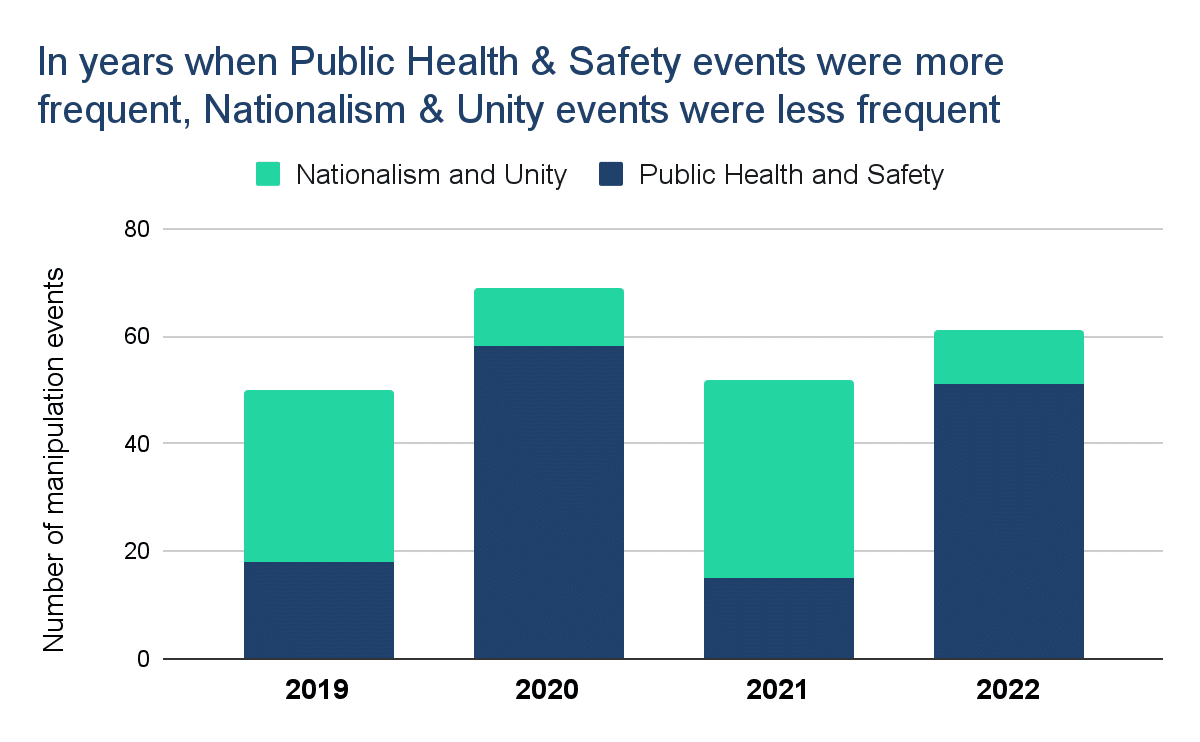

Beijing’s suite of nationalist messaging tools, including propaganda about the US and Japan, decreased when netizen discussion about––and censorship of––domestic issues increased.

- Nationalism on Weibo rose when discussions of COVID decreased, and dropped when COVID discussions increased (Figure 5).

- Anti-US content fell as Beijing worked to control conversations about COVID policies, lockdowns, and outbreaks.

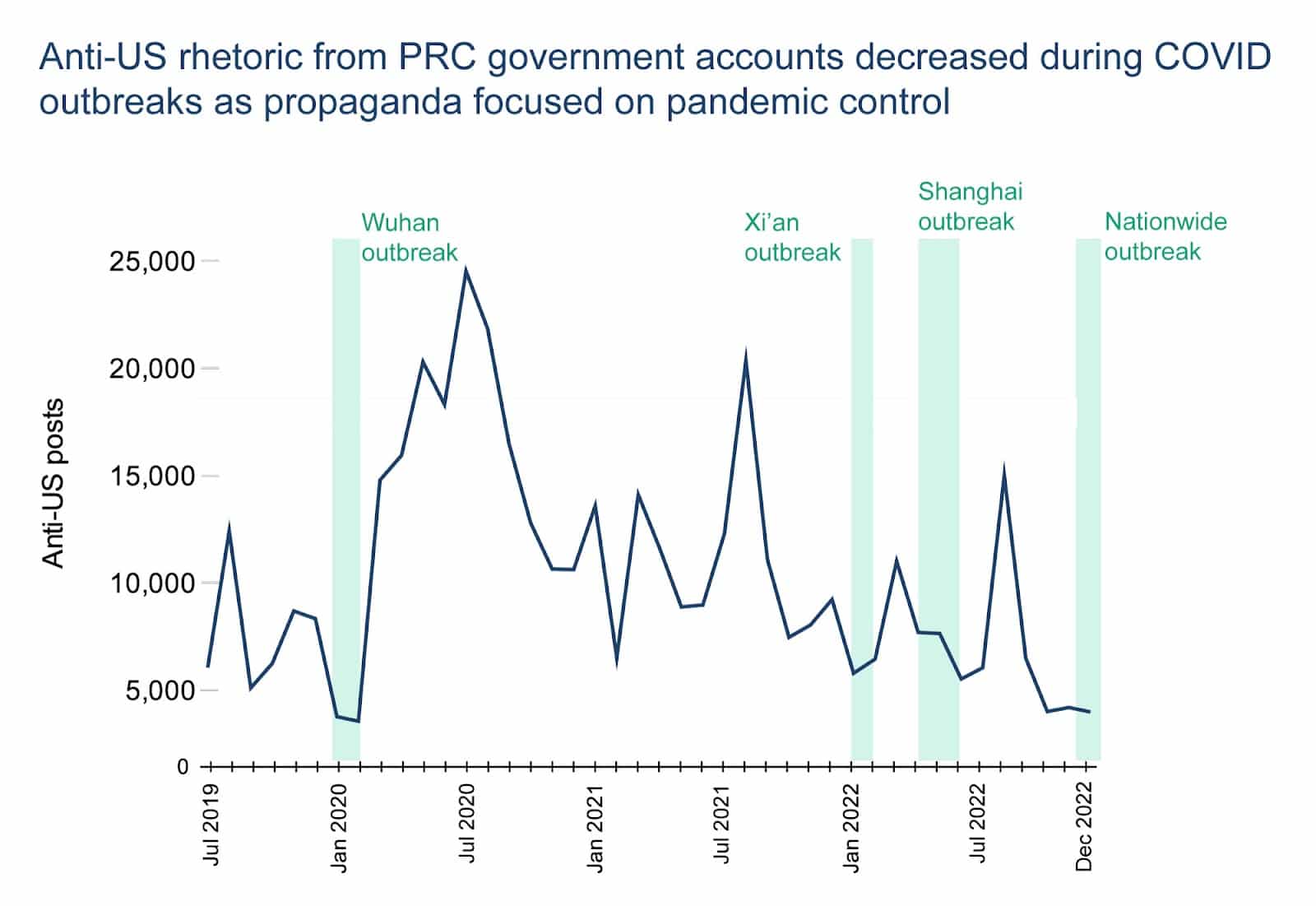

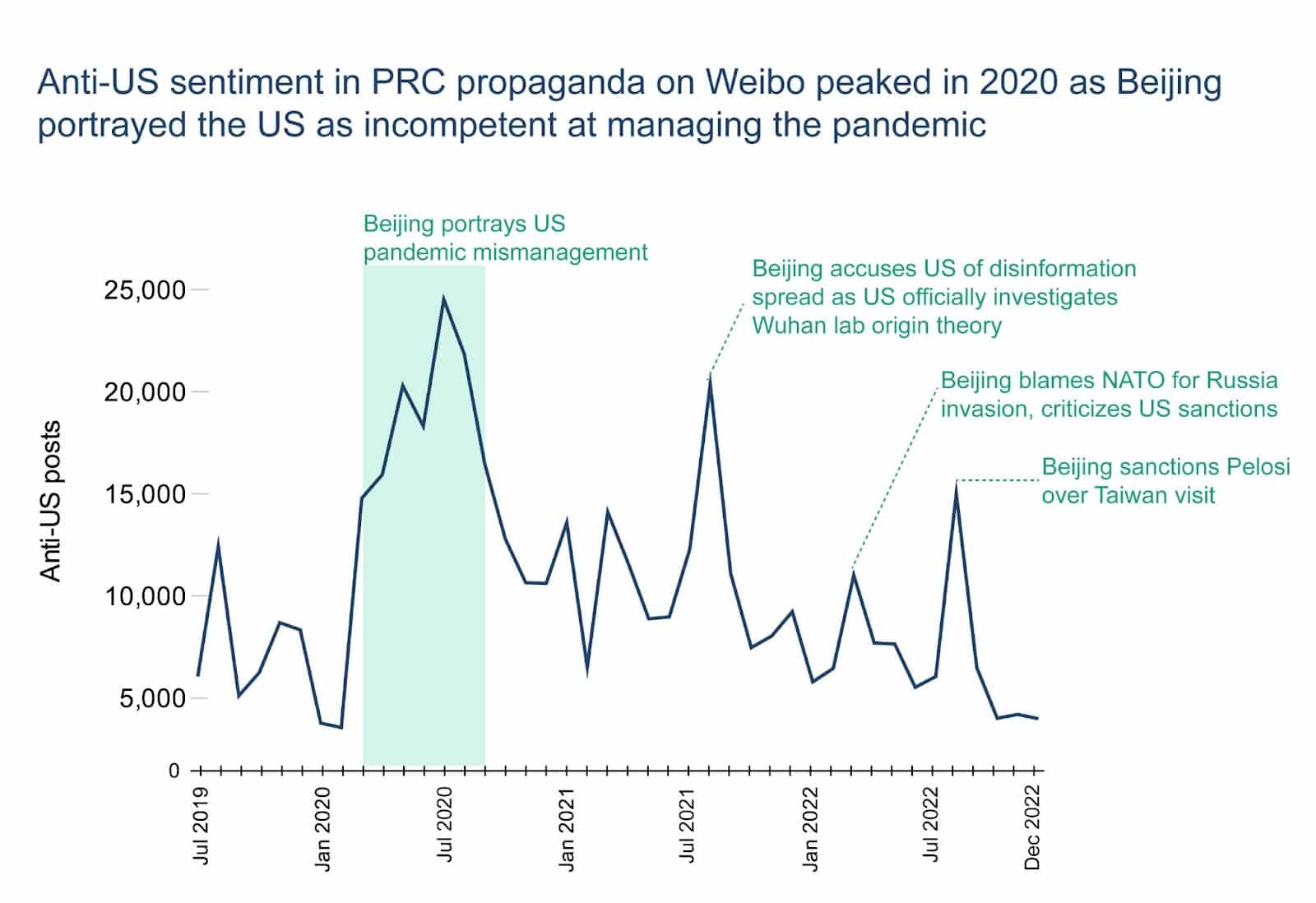

- M3 detected statistically significant drops in anti-US rhetoric in government propaganda on Weibo during the COVID lockdowns beginning in Shanghai in March 2022 and Wuhan in January 2020––China’s most well-known lockdown periods due to their size, duration, and negative effect on the economy (Figure 6).

- Anti-US sentiment expressed in PRC propaganda on Weibo peaked in March–July 2020 after China’s initial COVID cases had subsided, Wuhan’s lockdown lifted, and Beijing began to portray the US as incompetent at managing the pandemic (Figure 7).

Figure 6

Insight 4: Inauthentic, pro-Beijing accounts frequently push more controversial versions of Beijing’s narratives, suggesting official PRC messaging channels do not want to risk diplomatic pushback.

Inauthentic, pro-Beijing accounts sometimes express more incendiary reactions and varied narratives in response to global news events than official PRC messaging, suggesting at least one of the following dynamics:

- The PRC government does not coordinate every narrative produced by inauthentic accounts that Beijing likely hired to promote its messaging;

- The PRC intends to spread inflammatory messaging through covert channels that it would not risk announcing through official channels for fear of diplomatic pushback;

- The inauthentic accounts hired by Beijing are also serving other clients that push narratives which do not always align with Beijing’s; or

- The PRC uses inauthentic accounts to test out a variety of narratives while maintaining messaging discipline via its official accounts.

Data: M3 identified at least five instances of the PRC government and inauthentic messaging pushing more controversial or conflicting versions of Beijing’s narratives in response to global news events during September 2022–March 2023, including:

- Protests in Israel in March 2023,

- Australia-UK-US (AUKUS) summit in March 2023,

- Earthquake in Syria in February 2023,

- Pfizer’s COVID vaccines in January 2023,

- Russia’s retreat from Kharkiv Oblast in September–November 2022.

Reach out to the M3 team for more details.