Written by Jonathan Prokos

Our last blog post on Hashashin was almost four years ago[1]; since then the entire tool has been redesigned. Given the SafeDocs program is coming to a close and Hashashin is being transitioned into other work, it is time we provide an updated blog post outlining the approaches we tried and lessons learned through the process of developing Hashashin.

Disclaimer: This research was developed with funding from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). The views, opinions and/or findings expressed are those of the author and should not be interpreted as representing the official views or policies of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

tldr; What is Hashashin?

Hashashin utilizes statistical methods to compare functions within a binary. This allows us to identify similar functions across binaries. This is useful for identifying code reuse, malware, and other interesting properties of binaries.

You may find this tool useful if you are interested in:

- Identifying the libraries used within a binary + their versions

- Identifying code reuse across binaries

- Matching unknown binaries to known binaries

- Quickly identifying differences between patched binaries

- Performing any of these tasks at scale

Previous Approach

Our previous approach utilized Locality Sensitive Hashing (LSH)[2] along with the Weisfeiler Lehman Isomorphism Test (WLI)[3] to produce a graph representation of the basic blocks within a function which was used to compute similarity. While this approach works in theory, in practice this does not scale well.

Throughout the rest of this blog post I will go over my thought process and decisions made while redesigning Hashashin.

Background / Motivation

The primary focus when redesigning Hashashin was performance. While WLI provides an accurate estimate of graph similarity, it is far too slow for our application – scaling exponentially with the number of functions stored in the database.

While graph isomorphism is not able to handle these problems at scale, the idea of using LSH – also referred to as “fuzzy hashing” – remains at the core how Hashashin operates. The first step to redesigning this software was to perform a literature review of the current SoA in fuzzy hashing.

Literature Review

The most common use case of similar tools is in detecting malware and plagarism detection. Some of the papers I reviewed – in no particular order – during this process are listed below. Note many of the links have deprecated in the 8 months since access and most papers have minor differences between the published version and the version I read.

- Order Matters: Semantic-Aware Neural Networks for Binary Code Similarity Detection

- Topology-Aware Hashing for Effective Control Flow Graph Similarity Analysis

- BinSign: A Signature-Based Approach for Binary Code Similarity Detection

- Software Plagiarism Detection

- A stratified approach to function fingerprinting in program binaries using diverse features

- Neural Network-based Graph Embedding for Cross-Platform Binary Code Similarity Detection

- αDiff- Cross-Version Binary Code Similarity Detection with DNN

- Neural Machine Translation Inspired Binary Code Similarity Comparison beyond Function Pairs

- NIPS-2012-super-bit-locality-sensitive-hashing-Paper

- A Survey on Locality Sensitive Hashing Algorithms and their Applications

- A Survey of Binary Code Similarity

- How Machine Learning Is Solving the Binary Function Similarity Problem

- NIPS-2009-locality-sensitive-binary-codes-from-shift-invariant-kernels-Paper

- Efficient features for function matching between binary executables

Of these papers, BinSign[4] best encapsulated the design goals of this Hashashin refactor. In particular, we move away from a test of graph similarity to a comparison of extracted features. Additionally, the paper describes a methodology for generating a candidate set of similar functions which can be generated using a more efficient algorithm for which a deeper comparison can be utilized in a second step.

These ideas gave rise to the notion of a tiered hashing system in which a BinarySignature – consisting of many FunctionFeatures – can be compared against a database of other signatures efficiently using the minhash algorithm[9]. Many ideas for which features to use come from Efficient features for function matching between binary executables by Karamitas & Kehagias[5].

Initial Design

The first step to implementing this redesign is to develop a set of features which can be extracted from a function. While this list is configurable to the use case, by default[6] Hashashin extracts the following features using the BinaryNinja API[7]:

- Cyclomatic Complexity[8]

- Number of Instructions

- Number of Strings

- Maximum String Length

- Vertex Histogram

- Edge Histogram

- Instruction Histogram

- Dominator Signature

- Extracted Constants

- Extracted Strings

The extracted vertex and edge histograms are modifications of the solution posed in §IV.A of Karamitas[5]. The dominator signature is an exact implementation of what Karamitas calls digraph signatures from §IV.B. The instruction histogram relies on BinaryNinja’s MLIL.

Note the last two features – constants and strings – are just the first 64 and 512 bytes of a sorted list of the extracted feature respectively. This is done to create a staticly sized feature vector to compute matrix norms.

Once all function features have been computed, we use the minhash algorithm[9] to generate a BinarySignature which can be used to efficiently estimate jaccard similarity between other BinarySignatures.

Comparison

Under this tiered system we now have two ways to compare binaries: --fast-match and --robust-match. These options utilize both the minhash similarity estimate and true jaccard similarity respectively[10]. The former relies on the minhash generated BinarySignature. For the latter comparison, we compute similarity using matrix norms[11]. This returns a score between 0 and 2 for a collection of functions against another collection of functions. For estimating version, we compute this similarity between the candidate binary and the dataset of binaries each with their respective collection of functions.

Does it work?

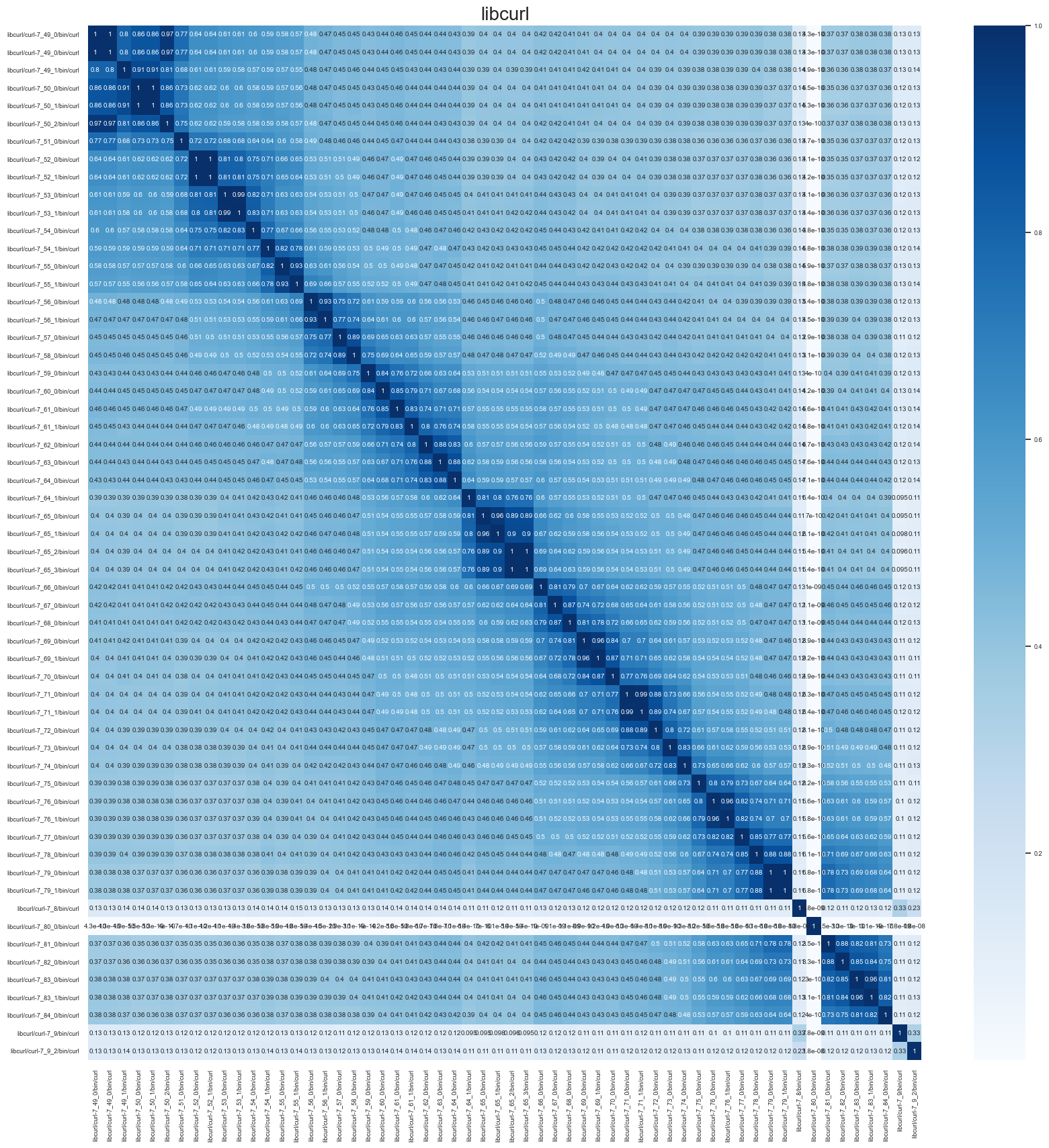

Yup, look at that graph! Our initial target for what this tool can be utilized for is identifying the unknown version of a known binary. To test this, we collect a dataset of adjacent binaries – including net-snmp, libcurl, and openssl.

Under net-snmp, we find that the --fast-match option works surprisingly well at determining not only the adjacent version for an unknown binary, but also its name under net-snmp (i.e. agentxtrap). However when introducing libcurl and openssl into the mix we find significant mismatching. We hypothesize this is due to net-snmp being a much smaller binary and therefore has far fewer “empty” functions. This is a problem which is addressed during our Elasticsearch upgrade which I will speak of later. A demo of these issues is shown in the Hashashin readme.

Despite the troubles with --fast-match false positives, the --robust-match comparison works very well. The following graphic shows the similarity between pairwise comparisons of 60 libcurl binaries (gathered from v7.8 through v7.84.0):

Ignoring the outliers – likely due to version string ordering & major version differences – we see a very strong correlation between adjacent versions of libcurl. This shows that given an unknown version of libcurl we can match it to a known version with a high degree of confidence. This is a very promising result for Hashashin’s future.

Transition

Given the results shown above, we begin looking to transition the Hashashin tool into other platforms at this point. Our first target for this transition is to utilize Hashashin within a platform called Pilot[12]. This is a COTS platform aimed to help developers and device vendors detect and remediate vulnerabilities in their firmware. The goal of this transition is to utilize Hashashin to pin potential net-snmp binaries to a known version with the intention of cross-referencing those versions against a database of known vulnerabilities.

While this work transitioned successfully, it highlighted a few issues with Hashashin moving forwards.

Growing Pains

At this point in Hashashin’s development, we rely on a SQLAlchemy database. This is great because we can use ORMs to quickly swap out our backend, but SQL has quickly become a major hindrance to Hashashin’s effectiveness. The largest issue with this current design – as shown in our Pilot transition – is the database recovery time before we even begin to perform comparisons. As a hotfix for the Pilot use-case, we instead store the net-snmp database as their respective numpy arrays to-be-compared in a pickle file. This is a major improvement in comparison time, but it is not a long-term solution.

Before we transition the Hashashin tool into other platforms we look into a full database redesign. Namely, we look to perform the bulk of similarity comparisons at the database level rather than the application level. This is where we begin to look into Elasticsearch[13].

Current Design

In addition to transitioning Hashashin into Pilot, we look to integrate the tool into our CircuitRE platform to perform Binary Similarity Analysis – this platform utilizes AI/ML capabilities to facilitate A.I.-assisted reverse engineering. As CircuitRE already utilizes Elasticsearch for much of its other processes, it is a natural fit to integrate into Hashashin.

Elasticsearch

At a high level, Elasticsearch is able to perform similarity comparisons between documents using a vector space model. While this provides some speedup to the --fast-match process, it provides very significant speedups to --robust-match which performs comparisons at the function level. When using Elasticsearch, we completely remove the --fast-match option and implement a generic match[14] function.

Elasticsearch Mapping

In order to utilize Elasticsearch for our comparisons, we must first define a mapping for our documents. Elasticsearch utilizes a flat document structure for lookups meaning we need to create a parent-child relationship between Binaries and their respective FunctionFeatures. Additionally, we decide to create static_properties as a feature vector which does not include the extracted strings or constants such that we can compare those features after the initial knn return. Our mapping can be found in ElasticSearchHashRepository.create; note all properties to be searched over must be stored at the top level of the mapping for knn-search. This means the notion of Binaries and Functions are both stored in the ES database as a single document type and bin_fn_relation notates which of the two the document is.

The Match Query

Now that we have a mapping, we can search over the database using knn-search. Below is pseudocode of our match query (full code here[14]):

Given a BinarySignature which contains a functionFeatureList

search_list = functions in functionFeatureList with cyclomatic complexity > 1

bulk_search = []

for each func in search_list:

header = {"index": self.config.index}

body = dict knn -> field = static_properties

add header and body to bulk_search

call msearch to search all queries

match_counts = dict()

for each response:

get closest hits by score

factor in constants and strings to update scores

if there is a tie for closest hit, randomly choose one

add the closest hit to match_counts and record its score

Update scores to be a percentage of total score

Return the top 5 matches sorting by the updated scores

As you can see, we first query the static_properties to return the top 5 closest hits for each function in the candidate binary then filter that down to get a closest match using the strings and constants. We then use those results to determine the likelihood the candidate binary belongs to a pre-computed binary already in the database based on how many of its functions match to the one stored in the db.

Future Work

In addition to general development fixes, there are a few key directions future Hashashin work can involve.

Performance Analysis

Hashashin has not been largely tested at scale as the REPO integration is ongoing. A major area of investigation to address is to determine which features are the most strongly correlated with true-positive matches. This will naturally facilitate additional feature extraction and more fine-tuned comparisons.

Feature Extraction

Hashashin currently relies on BinaryNinja to perform its extraction of functions and their respective features. A major hurdle for integrating this tool into other tools comes from the BinaryNinja licensing issues. Future work to implement a Ghidra extraction engine will alleviate this issue and allow Hashashin to be transitioned into more products at scale.

Plugin Development

Hashashin currently has a really terrible BinaryNinja plugin, it would be really nice to introduce this tool into the workflow of a reverse engineer.

Library Detection

We implement a net-snmp detector using Hashashin for our integration into Pilot, however there has not been much work into generalizing this process. A critical area of future work is to develop a system for generating a database of libraries to be used for this similarity analysis.

Conclusion / How Can You Use This?

If you are ingesting an unknown binary and would like to perform similarity analysis to recover its closest version, determine which libraries may be contained in the binary, or which parts of the binary may have changed, Hashashin will be a great tool for you to utilize.

Hashashin will be continuously changing and improving as we integrate it into more platforms – much of the reason these changes live on a develop branch. If you are interested in either contributing to or utilizing Hashashin, feel free to open a PR or issue on the Hashashin Github or reach out to the active maintainer at [email protected] (currently me – [email protected]).

Finally, I would like to shout out the Pilot and CircuitRE teams for their support developing this tool outside the SafeDocs program. If you would like to find out more about these tools or use them in your own work, please reach out to the Pilot team at [email protected] or view our whitepaper. If you would like to find out more about CircuitRE, please reach out to the team at [email protected].

[1] https://www.riverloopsecurity.com/blog/2019/12/binary-hashing-hashashin/

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Locality-sensitive_hashing

[3] https://davidbieber.com/post/2019-05-10-weisfeiler-lehman-isomorphism-test/

[4] https://inria.hal.science/hal-01648996/document

[5] https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8330221

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyclomatic_complexity

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/MinHash

[12] https://www.riverloopsecurity.com/files/whitepapers/pilot.pdf

[13] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elasticsearch

Distribution Statement A – Approved for Public Release, Distribution Unlimited