It’s easy to get lost in the stream of news about Russian disinformation and interference campaigns and assume Moscow has an unlimited ability to churn out inventive narratives, forcing its adversaries into a cycle of debunking that keeps them on the back foot. M3 takes a different approach: we quantify and contextualize hundreds of messaging campaigns. This reveals Russian messaging to be much more predictable than it may seem, leaving plenty of room for the US to preempt Kremlin criticism—and turn the tables on Moscow.

M3 Russia’s mid-year Biannual Manipulation Report is based on analysis of more than 450 messaging campaigns from over 300,000 official Kremlin posts on X (formerly Twitter)—think embassies and state-owned outlets like Sputnik. We also reviewed posts from pro-Kremlin, likely inauthentic accounts on X and Kremlin messaging for Russian audiences on domestic platforms VK, Telegram, and Channel 1 news to identify actionable trends that reveal Moscow’s messaging priorities and vulnerabilities.

Moscow’s strength: Spinning the news to undermine the West

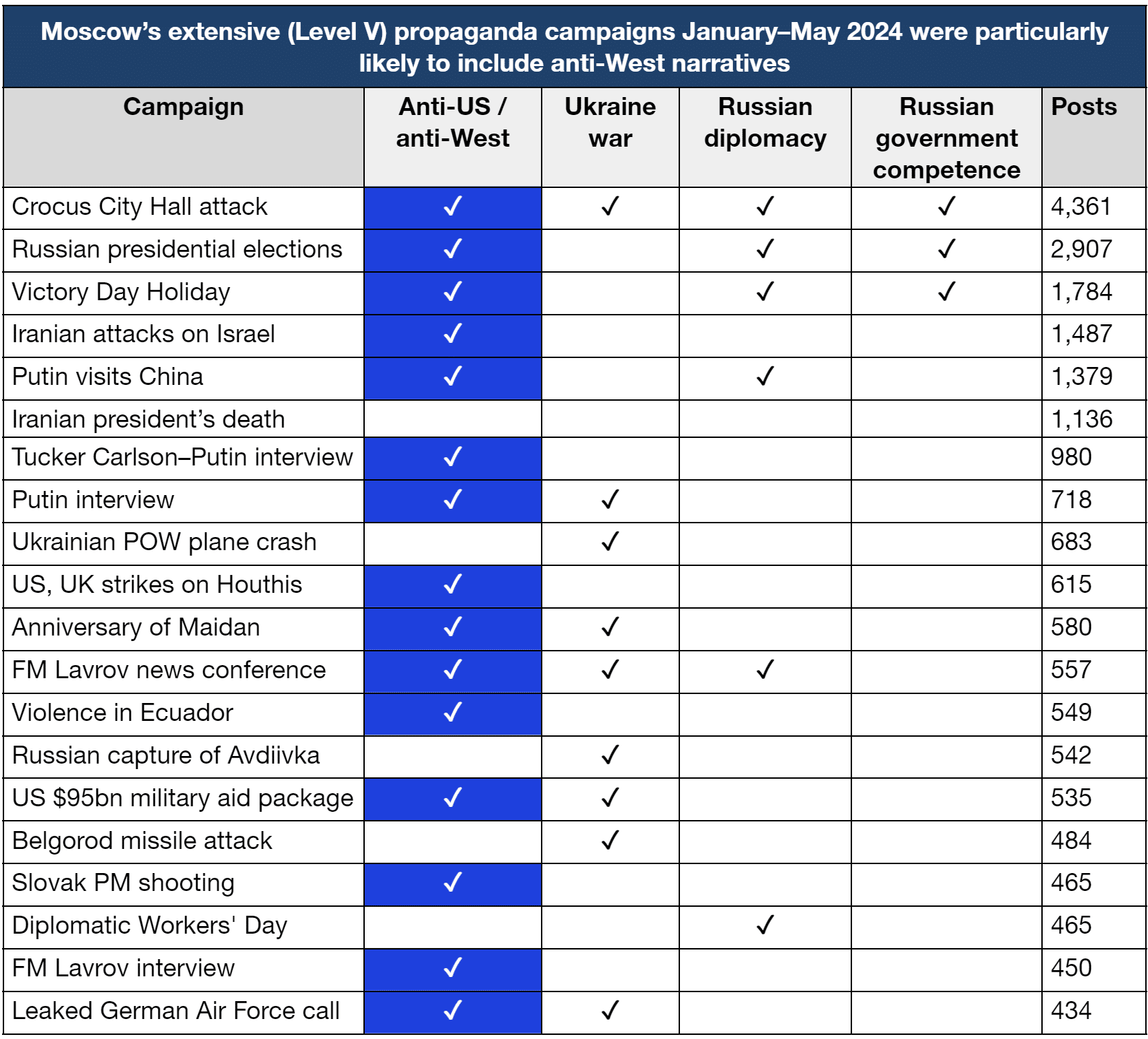

Moscow’s top priority in international messaging is undermining the US and its allies. This likely does not surprise anyone familiar with the Kremlin’s foreign policy for the past hundred years, most of which Moscow has spent considering the US its primary adversary. That said, the breadth of these anti-US narratives is still impressive. Moscow is more likely than not to respond to a major global news event with posts criticizing the US or US allies. You name it—riots in Ecuador, elections in India, electric cars in China—Moscow can find an anti-US angle. These narratives were even more common among the very largest campaigns—those in the top 0.1% by post volume on X. Figures 1 and 2

In particular, the war in Gaza has been the year’s largest propaganda windfall for Moscow. Moscow reoriented its messaging apparatus to portray the US and its ally Israel as unpopular warmongers. Official Kremlin accounts authored over 44,000 posts about the topic between January–June, consistently dominating Moscow’s coverage of the Middle East. Moscow also increased its post volumes in Arabic, which supplanted English as the top language of all Moscow’s global messaging because of the war. This pivot demonstrates Moscow’s capacity to surge messaging when the Kremlin sees a major opportunity to undermine US influence. Figure 3

However, there are also times when Moscow prefers to use a lighter touch in official messaging. Despite years of Western accusations that Moscow meddles in elections and spreads disinformation, the Kremlin seeks to protect the reputation of its state media outlets. In those cases, Moscow has a more discreet tool at its disposal: inauthentic, or bot, accounts can spread election-related narratives and disinformation on the government’s behalf. We see in our research that these inauthentic accounts help shape narratives favorable to Moscow at higher rates than do official Kremlin accounts. For example, pro-Kremlin, likely inauthentic accounts spread disinformation alleging the CIA and NATO were behind an assassination attempt on the Slovak prime minister in May and boosted the French far right during snap parliamentary elections in June–July. Figure 4

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Moscow’s weakness: Predictable narratives about topics closest to home

Moscow isn’t equally good at spinning the news in every direction, however. Moscow wants to portray itself as a country with many friends and a legitimate, competent government but can’t do so on the fly. Official accounts rarely portray Russia positively in reaction to breaking news stories—either because account operators face more red tape when writing about Russia or simply because Russia is often irrelevant to global news events. Instead, Moscow’s self-promotion usually requires real-world preparation, like the Russian foreign minister’s scheduled visit to Turkey or a military parade on a patriotic holiday. This is good news for the West, because prepared narratives are predictable narratives, and predictable narratives allow for preemptive counternarratives. Figure 5

Moscow can’t even muster dynamic messaging about the topic it probably cares about most: Ukraine. You would think that if Moscow could overhaul its messaging strategy to capitalize on the war in Gaza, it would put even more effort toward shaping narratives on its own war. That may have been true right after the invasion, when Moscow leaned into all kinds of colorful disinformation campaigns, like accusing Ukranians of being Nazis and Kyiv of creating biological weapons—with the US’s help, of course. Two years later, however, Moscow is still harping on those same narratives, while current events—US aid for Ukraine and Russian victories in Kharkiv Oblast, for instance—barely make a dent. Figure 6

It’s a different story inside Russia. For domestic audiences of state-owned television, VK, and Telegram, Moscow rarely bothers with anti-Ukraine narratives anymore, focusing instead on the latest village Moscow has “liberated” or the latest Western tank it has captured. We see this trend of focusing on Moscow’s competence over Ukraine’s villainy for domestic audiences in general and also in specific, high-profile narratives, like disinformation that Ukraine sponsored a March terrorist attack on Moscow. Moscow’s differing messaging strategies reveals different priorities: abroad, Moscow is still trying to justify starting the war, while at home Moscow seeks to show enough progress to justify continuing it. Figure 7

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Obtaining information advantage: exploit trends in Kremlin messaging to establish narratives, not just react with counternarratives

Counteracting Moscow’s strength in anti-West messaging requires a defensive strategy, but not a reactive one. There’s no reason to wait and see if Moscow will tie an emerging crisis somewhere in the world to Western interference—no matter how unrelated it may seem, we should assume the Kremlin will find a way. Immediate messaging about the US stance on breaking news—in the relevant local languages—will blunt the effectiveness of Moscow’s narratives. When Moscow hides its narratives behind inauthentic accounts, we must expose them. The US government and other actors do this often, yet still only catch the tip of the iceberg. More resources are needed for projects like M3 that seek to not only identify but quantify and contextualize Moscow’s inauthentic influence systematically so we can prioritize our efforts—and better understand Moscow’s priorities.

The West can do better than merely defending. A robust information advantage strategy would also go on the offense, forcing Moscow to expend resources reacting rather than investing its resources to shape narratives about Russia. The US can predict nearly all of Moscow’s self-promotion in the information space by keeping tabs on what the Russian government is planning to do in the physical world—a strength of our intelligence agencies, as declassified releases prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine proved. That means that the US government can push timely, tailored narratives revealing Russia to be unreliable, authoritarian, and weak before Moscow can launch campaigns portraying itself as reliable, legitimate, and strong.

Moscow believes three great powers—the US, Russia, and China—have the right to compete for influence over other countries, whose peoples have little independent agency. We can gain information advantage by shaping narratives about US influence before Moscow can manipulate them and proactively exposing Moscow’s malign influence, giving global populations the information they need to choose partners wisely and chart their own futures.

Two Six Tech’s Media Manipulation Monitor (M3) tracks Russian and Chinese information operations. For more data-backed, actionable insights about Moscow’s messaging, please reach out to [email protected] to request a copy of our Russia Biannual Manipulation Report (BAM) and to learn more about our analytic products analyzing Kremlin messaging every week.